6. Regression Analysis¶

Regression analysis is a statistical technique that allows us to determine the relationship between two or more quantitative variables in order to predict a response or outcome variable from one or more of them. This methodology is frequently employed in a variety of fields, including business, social and behavioral sciences, biology, and many more.

Here are a few examples of applications:

In business, the relationship between product sales and advertising expenditures can be used to forecast product sales.

A financial firm may wish to know the top five causes that drive a customer to default in order to reduce risk in their portfolio.

A automobile insurance firm might use expected claims to Insured Declared Value ratio to create a suggested premium table using linear regression. The risk might be calculated based on the car’s characteristics, the driver’s information, or demographics.

The goal of regression is to create a model that expresses the relationship between a response \({\displaystyle Y_{i}} \in R^n\) and a set of one or more (independent) variables \({\displaystyle X_{i}} \in R^n\). We can use the model to predict the response \({\displaystyle Y_{i}}\) based on the factors (or variables).

The following elements are included in regression models:

The unknown parameters, which are frequently denoted as a scalar or vector \(\beta\).

The independent variables, which are observed in data and are frequently expressed as a vector \({\displaystyle X_{i}}\) (where \({\displaystyle i}\) denotes a data row).

The dependent variable, which can be seen in data and is frequently represented by the scalar \(Y_{i}\).

The error terms, which are not readily visible in data and are frequently represented by the scalar \(e_{i}\).

Most regression models propose that \(Y_{i}\) is a function of \(X_{i}\) and \(\beta\),

In other words, regression analysis aims to find the function \(f(X_{i},\beta)\) that best matches the data. The function’s form must be supplied in order to do regression analysis. The form of this function is sometimes based on knowledge of the relationship between \(X_{i}\) and \(Y_{i}\). If such information is not available, a flexible or convenient form is adopted.

6.1. Simple linear regression¶

The simplest model to consider is a linear model, in which the response \({\displaystyle Y_{i}}\) is linearly proportional to the variables \({\displaystyle X_{i}}\):

6.3. Multivariate Analysis¶

Our next analysis is to estimate the association between two or more independent variables and one dependent variable. Multiple linear regression will be used to answer the following:

The degree to which two or more independent variables and one dependent variable are related (e.g. how strong the relationship is between independent variables (age, bmi, and smoker) and dependent variable (charges)).

The value of the dependent variable at a given value of the independent variables (e.g. age, bmi, and smoking status addition)

df = pd.read_csv('/Users/Kaemyuijang/SCMA248/Data/insuranceKaggle.csv')

df.head()

| age | sex | bmi | children | smoker | region | charges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | female | 27.900 | 0 | yes | southwest | 16884.92400 |

| 1 | 18 | male | 33.770 | 1 | no | southeast | 1725.55230 |

| 2 | 28 | male | 33.000 | 3 | no | southeast | 4449.46200 |

| 3 | 33 | male | 22.705 | 0 | no | northwest | 21984.47061 |

| 4 | 32 | male | 28.880 | 0 | no | northwest | 3866.85520 |

6.3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)¶

We will perform exploratory data analysis to analyze data quality as well as uncover hidden relationships between variables. In this exercise, I’ll go through three strategies relevant to regression analysis:

Multivariate analysis

Preprocessing categorical variables

Correlation Analysis

6.3.1.1. Multivariate analysis¶

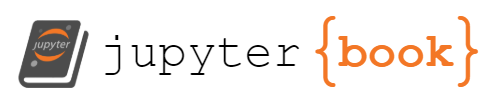

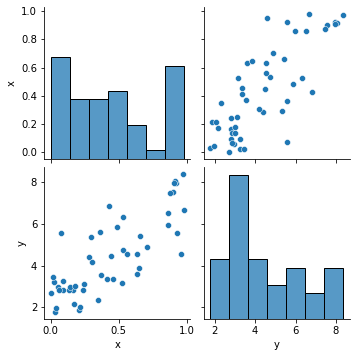

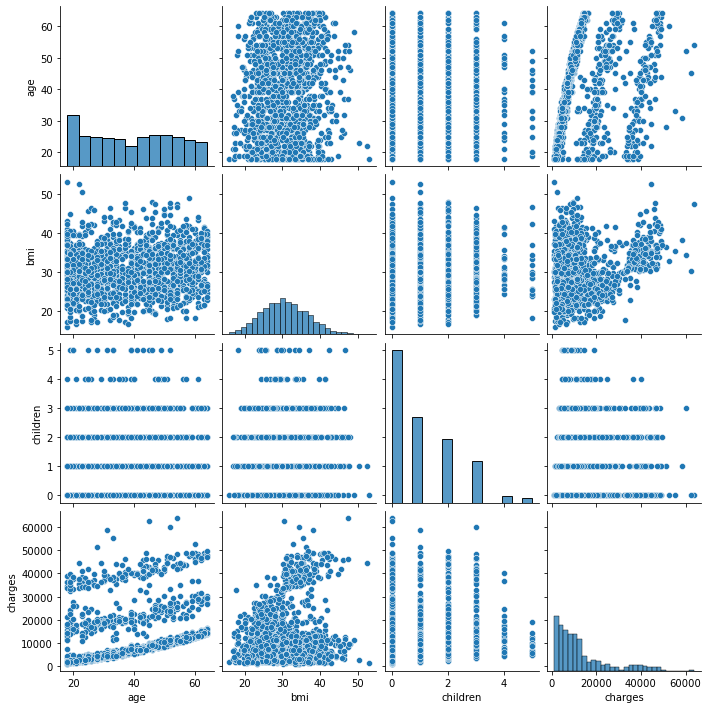

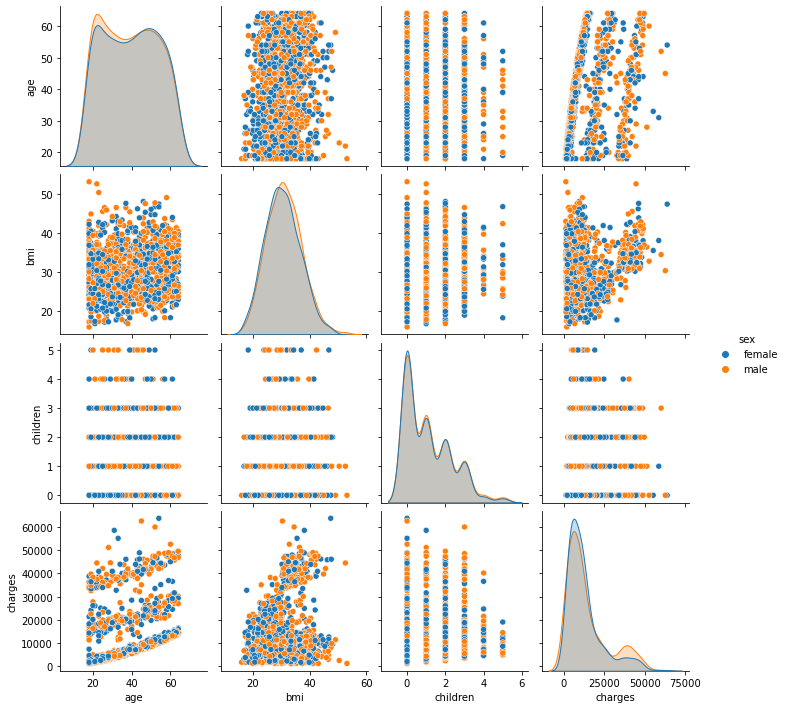

We have already created a pairs plot to shows the distribution of single variables as well as the relationships between them.

sns.pairplot(df)

<seaborn.axisgrid.PairGrid at 0x124a95290>

Note Our dataset contains both continuous and categorical variables. However, the pairs plot shows only the relationship of the continuous variables.

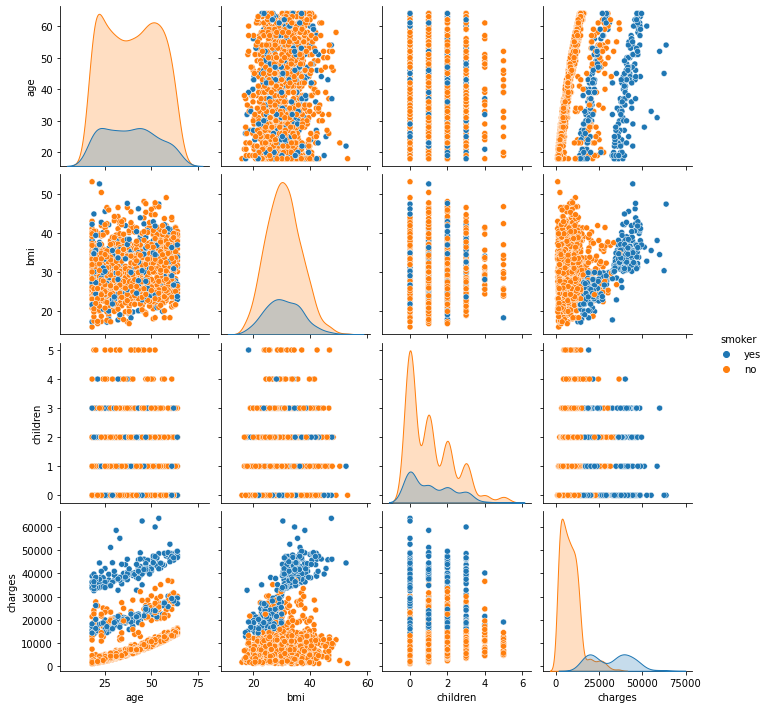

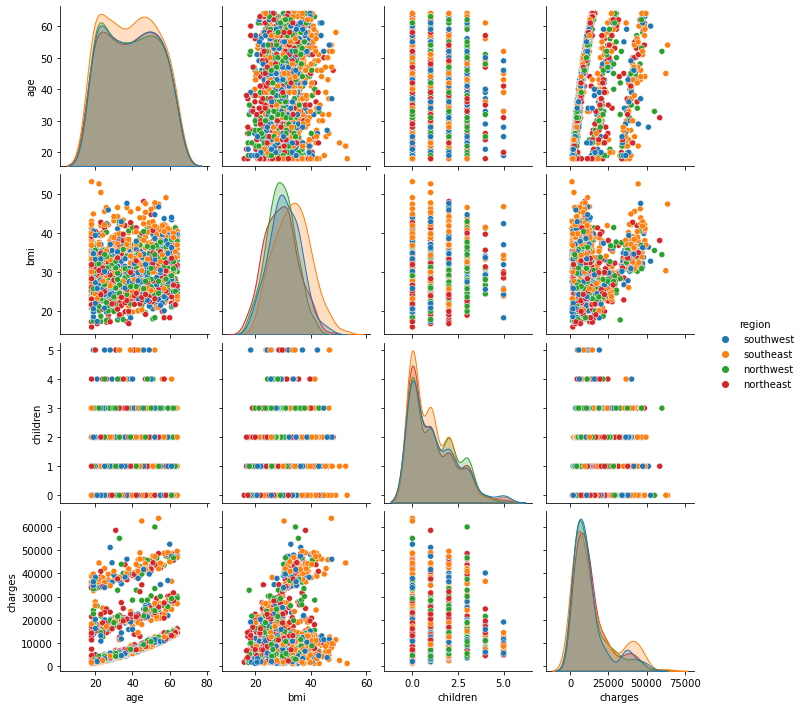

In Seaborn, pairs plots (scatter plots or box plots) can take an additional hue argument to add another variable for comparison (e.g., for comparison between different categories).

6.3.1.2. Pairs Plot with Color by Category¶

Consider making the categorical variable the legend. To do this, we first create the lists of numeric variables num_list and categorical variables cat_list.

df.columns

Index(['age', 'sex', 'bmi', 'children', 'smoker', 'region', 'charges'], dtype='object')

# Asserting column(s) data type in Pandas

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/28596493/asserting-columns-data-type-in-pandas

import pandas.api.types as ptypes

num_list = []

cat_list = []

for column in df.columns:

#print(column)

if ptypes.is_numeric_dtype(df[column]):

num_list.append(column)

elif ptypes.is_string_dtype(df[column]):

cat_list.append(column)

# pairplot with hue

for i in range(0,len(cat_list)):

hue_cat = cat_list[i]

sns.pairplot(df, hue = hue_cat)

# df.head()

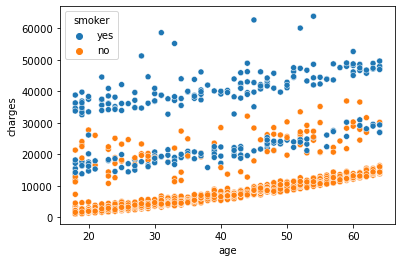

sns.scatterplot(x='age',y='charges', hue = 'smoker', data =df)

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='age', ylabel='charges'>

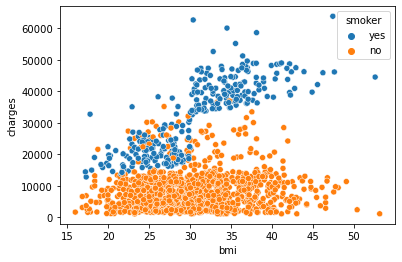

sns.scatterplot(x='bmi',y='charges', hue = 'smoker', data =df)

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='bmi', ylabel='charges'>

We can observe that age, bmi, and smoking status are all correlated to the target variable charges. Charges increase as you become older and your BMI rises. The Smoker variable clearly separates the data set into two groups. It suggests that the feature “smoker” could be a good predictor of charges.

Conclusion: age, bmi, and smoker are all key factors in determining charges. In the data set, sex and region do not exhibit any significant patterns.

Exercise Use plotnine to create the two scatter plots above.

6.3.1.3. Preprocessing categorical variables¶

Categorical variables cannot be handled by most machine learning algorithms unless they are converted to numerical values. The categorical variables must be preprocessed before they may be used. We must transform these categorical variables to integers in order for the model to comprehend and extract useful information.

We can encode these categorical variables as integers in a variety of ways and use them in our regression analysis. We’ll take a look at two of them, including

One Hot Encoding

Label Encoding

6.3.1.4. One Hot Encoding¶

In this method, we map each category to a vector that comprises 1 and 0, indicating whether the feature is present or not. The number of vectors is determined by the number of feature categories. If the number of categories for the feature is really large, this approach produces many columns, which considerably slows down the model processing.

The get_dummies function in Pandas is quite simple to use. The following is a sample DataFrame code:

df_encoding1 = pd.get_dummies(df, columns = cat_list)

df_encoding1

| age | bmi | children | charges | sex_female | sex_male | smoker_no | smoker_yes | region_northeast | region_northwest | region_southeast | region_southwest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 30.970 | 3 | 10600.54830 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1334 | 18 | 31.920 | 0 | 2205.98080 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1335 | 18 | 36.850 | 0 | 1629.83350 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1336 | 21 | 25.800 | 0 | 2007.94500 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1337 | 61 | 29.070 | 0 | 29141.36030 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

1338 rows × 12 columns

Alternative to the above command, we also add two arguments

drop_first=Trueto get k-1 dummies out of k categorical levels by removing the first level,

*columns=['smoker','sex'] to specify the column names in the DataFrame to be encoded.

# Alternative to the above command, we also specify drop_first=True

df_encoding1 = pd.get_dummies(data=df, columns=['smoker','sex'], drop_first=True)

# print(df.head())

# df_encoding1.head()

# rename the column names

df_encoding1 = df_encoding1.rename(columns={"smoker_1":"smoker_yes","sex_1":"sex_male"})

df_encoding1

| age | bmi | children | region | charges | smoker_yes | sex_male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | southwest | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | southeast | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | southeast | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | northwest | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | northwest | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 30.970 | 3 | northwest | 10600.54830 | 0 | 1 |

| 1334 | 18 | 31.920 | 0 | northeast | 2205.98080 | 0 | 0 |

| 1335 | 18 | 36.850 | 0 | southeast | 1629.83350 | 0 | 0 |

| 1336 | 21 | 25.800 | 0 | southwest | 2007.94500 | 0 | 0 |

| 1337 | 61 | 29.070 | 0 | northwest | 29141.36030 | 1 | 0 |

1338 rows × 7 columns

6.3.1.5. Label Encoding¶

In this encoding, each category in this encoding is given a number between 1 and N (where N is the number of categories for the feature). One fundamental problem with this technique is that there is no relationship or order between these classes, despite the fact that the algorithm may treat them as such. (region0 < region1 < region2 and 0 < 1 < 2) is an example of what it might look like. The data-frame has the following Scikit-learn code:

df = pd.read_csv('/Users/Kaemyuijang/SCMA248/Data/insuranceKaggle.csv')

from sklearn import preprocessing

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

df_encoding2 = df

for i in cat_list:

df_encoding2[i] = LabelEncoder().fit_transform(df[i])

df_encoding2

| age | sex | bmi | children | smoker | region | charges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 0 | 27.900 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 16884.92400 |

| 1 | 18 | 1 | 33.770 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1725.55230 |

| 2 | 28 | 1 | 33.000 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 4449.46200 |

| 3 | 33 | 1 | 22.705 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21984.47061 |

| 4 | 32 | 1 | 28.880 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3866.85520 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 1 | 30.970 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 10600.54830 |

| 1334 | 18 | 0 | 31.920 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2205.98080 |

| 1335 | 18 | 0 | 36.850 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1629.83350 |

| 1336 | 21 | 0 | 25.800 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2007.94500 |

| 1337 | 61 | 0 | 29.070 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 29141.36030 |

1338 rows × 7 columns

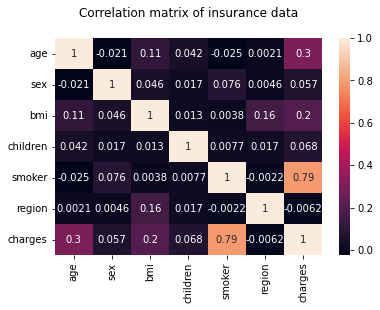

6.3.1.6. Correlation Analysis¶

The linear correlation between variable pairs is investigated using correlation analysis. This may be accomplished by combining the corr() and sns.heatmap() functions.

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

hm = sns.heatmap(df.corr(), annot = True)

hm.set(title = "Correlation matrix of insurance data\n")

plt.show()

Note: The correlation matrix also confirms that age, bmi, and smoker are all key factors in determining charges.

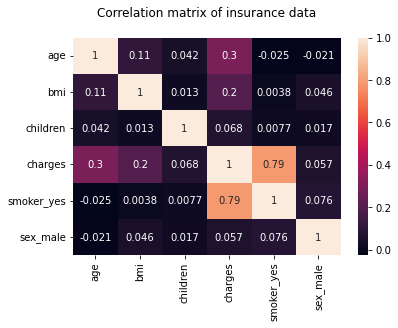

In what follows, we will use one hot encoding for the smoker category.

See https://python-graph-gallery.com/91-customize-seaborn-heatmap for customization of heatmap using seaborn.

#df = pd.read_csv('/Users/Kaemyuijang/SCMA248/Data/insuranceKaggle.csv')

#df = pd.get_dummies(df, columns = cat_list)

hm = sns.heatmap(df_encoding1.corr(), annot = True)

hm.set(title = "Correlation matrix of insurance data\n")

plt.show()

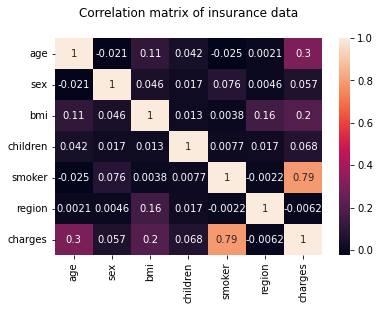

hm = sns.heatmap(df_encoding2.corr(), annot = True)

hm.set(title = "Correlation matrix of insurance data\n")

plt.show()

6.3.2. Multiple Linear Regression¶

Multiple inputs and a single output are possible in multiple linear regression. We’ll look at how numerous input variables interact to affect the output variable, as well as how the calculations differ from those of a simple linear regression model. We’ll also use Python’s Statsmodel to create a multiple regression model.

Recall that the fitted regression model equation is

Multiple regression model

Here, \(Y\) is the output variable, and \(X_1,\ldots,X_p\) terms are the corresponding input variables.

Hence, our Linear Regression model can now be expressed as:

Finding the values of these constants (β) is the task of the regression model, minimizing the error function and fitting the best line or hyperplane (depending on the number of input variables).

This is done by minimizing the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS), which is obtained by squaring the differences between the actual and predicted results.

6.3.2.1. Building the model and interpreting the coefficients¶

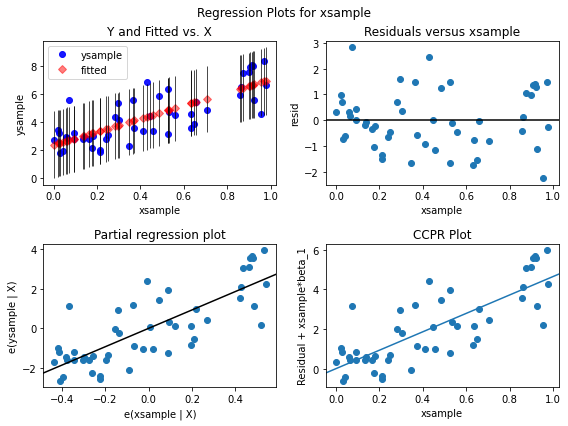

Similar to linear regression analysis, the results can be obtained by running the following code:

Fit and summary:

df_encoding1

| age | bmi | children | region | charges | smoker_yes | sex_male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | southwest | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | southeast | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | southeast | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | northwest | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | northwest | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 30.970 | 3 | northwest | 10600.54830 | 0 | 1 |

| 1334 | 18 | 31.920 | 0 | northeast | 2205.98080 | 0 | 0 |

| 1335 | 18 | 36.850 | 0 | southeast | 1629.83350 | 0 | 0 |

| 1336 | 21 | 25.800 | 0 | southwest | 2007.94500 | 0 | 0 |

| 1337 | 61 | 29.070 | 0 | northwest | 29141.36030 | 1 | 0 |

1338 rows × 7 columns

model3 = smf.ols(formula='charges ~ age + bmi + smoker_yes', data=df_encoding1).fit()

model3.summary()

| Dep. Variable: | charges | R-squared: | 0.747 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model: | OLS | Adj. R-squared: | 0.747 |

| Method: | Least Squares | F-statistic: | 1316. |

| Date: | Sat, 09 Jul 2022 | Prob (F-statistic): | 0.00 |

| Time: | 17:36:44 | Log-Likelihood: | -13557. |

| No. Observations: | 1338 | AIC: | 2.712e+04 |

| Df Residuals: | 1334 | BIC: | 2.714e+04 |

| Df Model: | 3 | ||

| Covariance Type: | nonrobust |

| coef | std err | t | P>|t| | [0.025 | 0.975] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -1.168e+04 | 937.569 | -12.454 | 0.000 | -1.35e+04 | -9837.561 |

| age | 259.5475 | 11.934 | 21.748 | 0.000 | 236.136 | 282.959 |

| bmi | 322.6151 | 27.487 | 11.737 | 0.000 | 268.692 | 376.538 |

| smoker_yes | 2.382e+04 | 412.867 | 57.703 | 0.000 | 2.3e+04 | 2.46e+04 |

| Omnibus: | 299.709 | Durbin-Watson: | 2.077 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prob(Omnibus): | 0.000 | Jarque-Bera (JB): | 710.137 |

| Skew: | 1.213 | Prob(JB): | 6.25e-155 |

| Kurtosis: | 5.618 | Cond. No. | 289. |

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

Quantities of interest can be extracted directly from the fitted model. Type dir(results) for a full list. Here are some examples:

print("Parameters: ", model3.params)

print("R2: ", model3.rsquared)

Parameters: Intercept -11676.830425

age 259.547492

bmi 322.615133

smoker_yes 23823.684495

dtype: float64

R2: 0.7474771588119513

6.3.2.2. Fitted multiple regression function¶

Based on the previous results, the equation to predict the output variable using age, bmi, and smoker yes as input would be as follows:

6.3.2.3. Example of calculating fitted values¶

If sample data with actual output value 8240.5896 has

age = 46,

bmi = 33.44 and *smoker yes = 0,

then we substitute the value of age for age, bmi and smoker_yes in the previous equation, we get

charges = 11050.6042276108 = - 11676.83042519 + (259.5474915546) + (322.6151328233.44) + (23823.68449531 * 0)

If we construct a multiple linear regression model and use age, bmi, and smoker yes as input variables, a 46-year-old person will have to pay an insurance charge of 11050.6042276108.

We can see that the anticipated value is rather close to the real value. As a result, we can conclude that the Multiple Linear Regression model outperforms the Simple Linear Regression model.

Note Based on the linear regression result, equation to predict output variable using only age as an input would be like,

charges = (257.72261867 * age) + 3165.88500606

If we will put value of age = 46 in above equation then,

charges = 15021.12546488 = (257.72261867 * 46) + 3165.88500606

Here we can see that the predicted value is almost double. So we can say that the simple linear regression model does not work well.

x=df[['age']]

y=df[['charges']]

predictions = model1.predict(x)

df['slr_result'] = predictions

df['slr_error'] = df['charges'] - df['slr_result']

x=df_encoding1[['age','bmi','smoker_yes']]

y=df_encoding1[['charges']]

predictions = model3.predict(x)

df_encoding1['mlr_result'] = predictions

df_encoding1['mlr_error'] = df_encoding1['charges'] - df_encoding1['mlr_result']

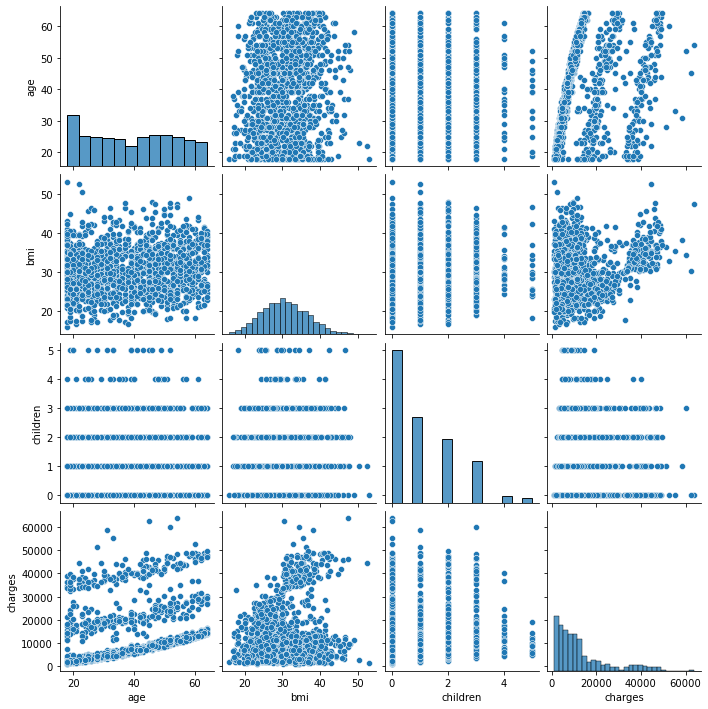

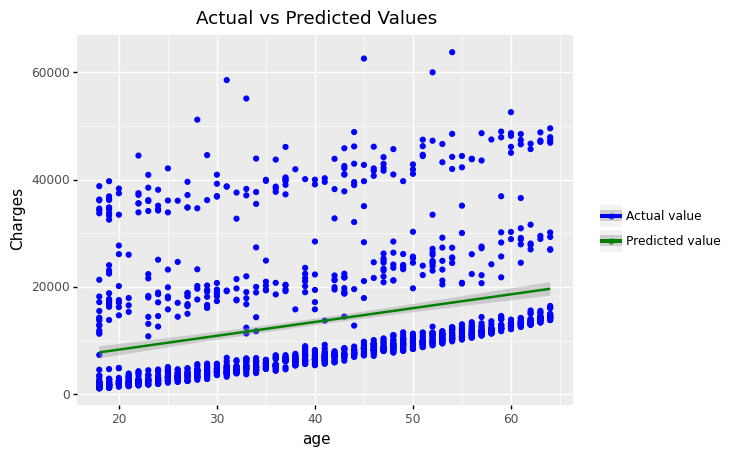

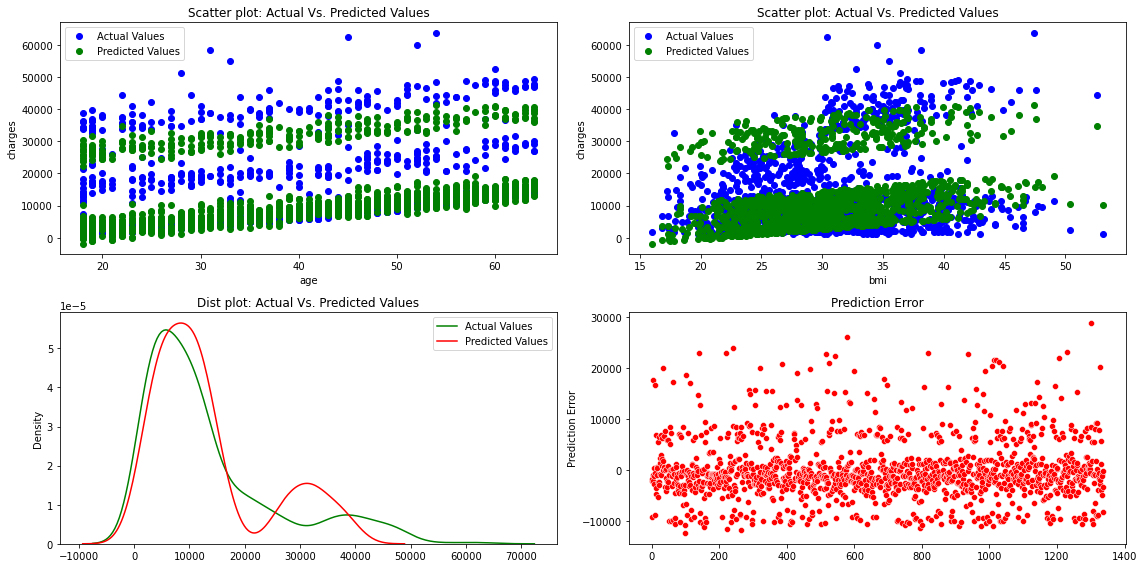

fig, axes =plt.subplots(2,2, figsize=(16,8))

axes[0][0].plot(x['age'], y,'bo',label='Actual Values')

axes[0][0].plot(x['age'], predictions,'go',label='Predicted Values')

axes[0][0].set_title("Scatter plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[0][0].set_xlabel("age")

axes[0][0].set_ylabel("charges")

axes[0][0].legend()

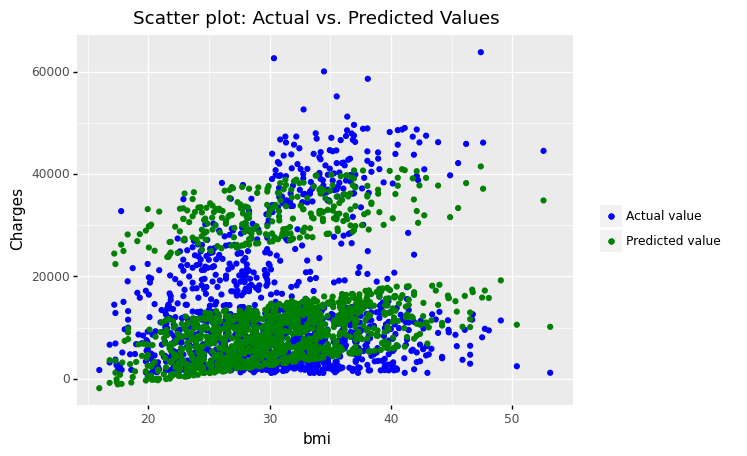

axes[0][1].plot(x['bmi'], y,'bo',label='Actual Values')

axes[0][1].plot(x['bmi'], predictions,'go',label='Predicted Values')

axes[0][1].set_title("Scatter plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[0][1].set_xlabel("bmi")

axes[0][1].set_ylabel("charges")

axes[0][1].legend()

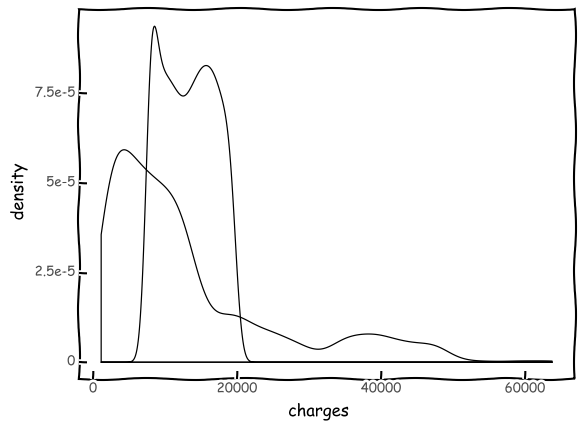

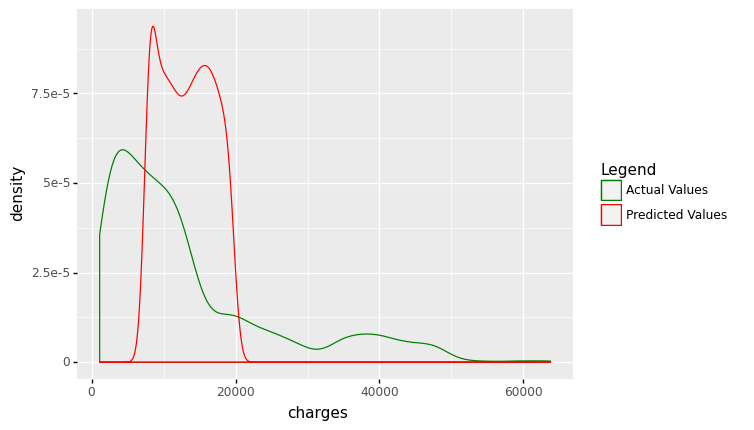

sns.distplot(y, hist=False, color="g", label="Actual Values",ax=axes[1][0])

sns.distplot(predictions, hist=False, color="r", label="Predicted Values" , ax=axes[1][0])

axes[1][0].set_title("Dist plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[1][0].legend()

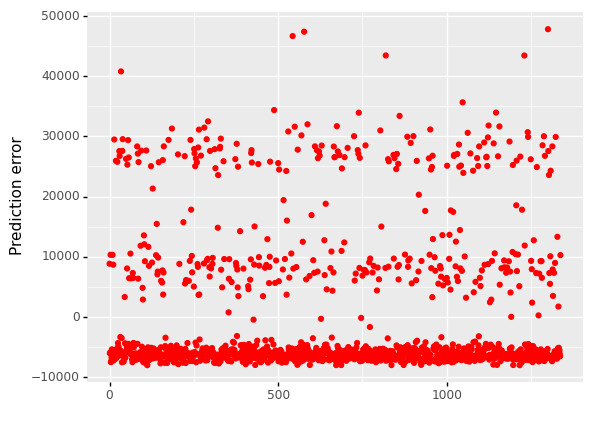

sns.scatterplot(x=y.index,y='mlr_error',data=df_encoding1,color="r", ax=axes[1][1])

axes[1][1].set_title("Prediction Error")

axes[1][1].set_ylabel("Prediction Error")

fig.tight_layout()

/Users/Kaemyuijang/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/seaborn/distributions.py:2619: FutureWarning: `distplot` is a deprecated function and will be removed in a future version. Please adapt your code to use either `displot` (a figure-level function with similar flexibility) or `kdeplot` (an axes-level function for kernel density plots).

/Users/Kaemyuijang/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/seaborn/distributions.py:2619: FutureWarning: `distplot` is a deprecated function and will be removed in a future version. Please adapt your code to use either `displot` (a figure-level function with similar flexibility) or `kdeplot` (an axes-level function for kernel density plots).

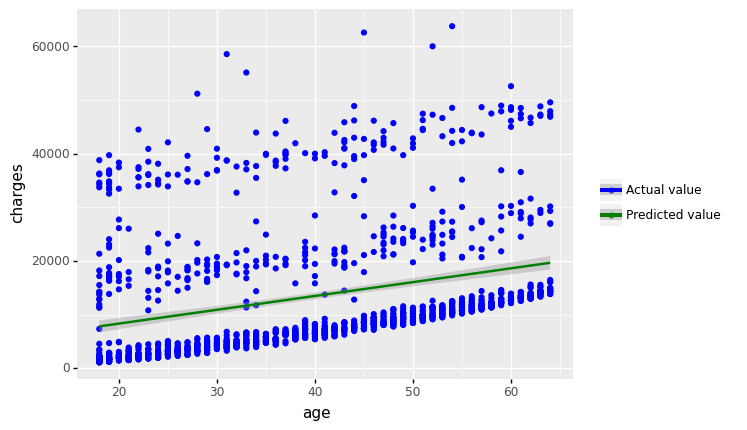

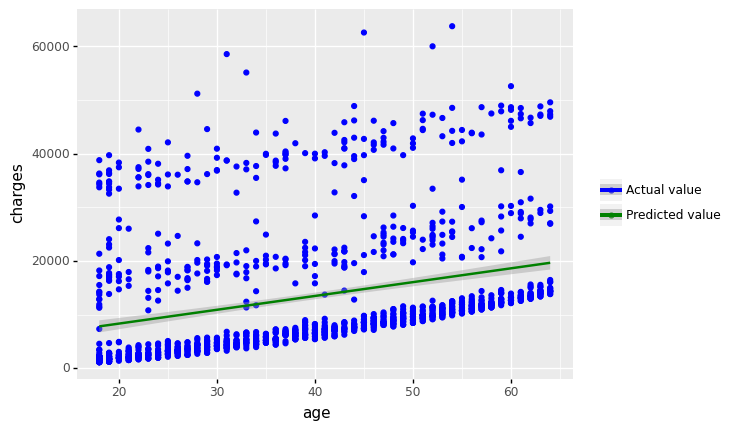

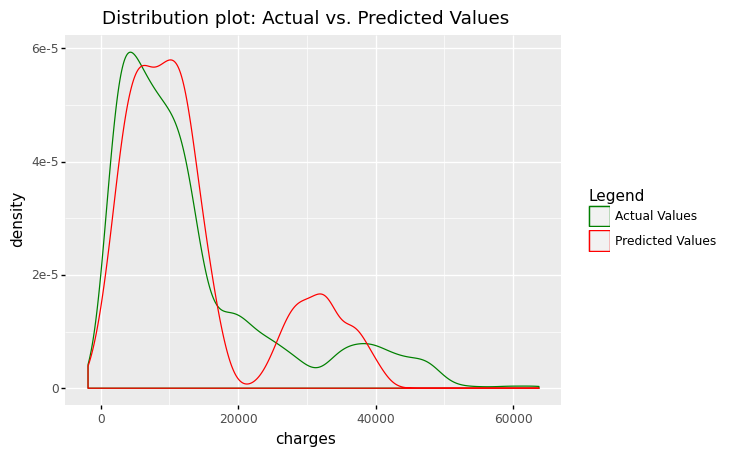

The figures show that the multiple linear regression model fits better than the simple linear regression because the predicted values are close to the observed data values

(

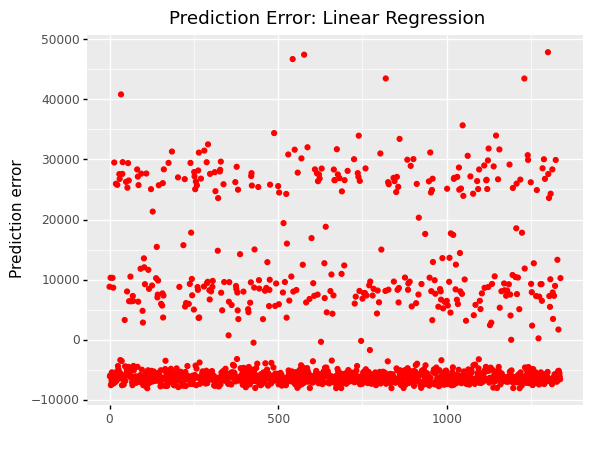

ggplot(df, aes(x='df.index'))

+ geom_point(aes(y='slr_error'),color='red')

+ labs(x = ' ', y='Prediction error')

+ labs(title = 'Prediction Error: Linear Regression')

)

<ggplot: (311177589)>

# print('length of x:',len(x))

#print('length of y:',len(y))

# print(df_encoding1)

df_encoding1

| age | bmi | children | region | charges | smoker_yes | sex_male | mlr_result | mlr_error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | southwest | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 | 26079.218615 | -9194.294615 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | southeast | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 | 3889.737458 | -2164.185158 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | southeast | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 | 6236.798721 | -1787.336721 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | northwest | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 | 4213.213387 | 17771.257223 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | northwest | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 | 5945.814340 | -2078.959140 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 30.970 | 3 | northwest | 10600.54830 | 0 | 1 | 11291.934816 | -691.386516 |

| 1334 | 18 | 31.920 | 0 | northeast | 2205.98080 | 0 | 0 | 3292.899462 | -1086.918662 |

| 1335 | 18 | 36.850 | 0 | southeast | 1629.83350 | 0 | 0 | 4883.392067 | -3253.558567 |

| 1336 | 21 | 25.800 | 0 | southwest | 2007.94500 | 0 | 0 | 2097.137324 | -89.192324 |

| 1337 | 61 | 29.070 | 0 | northwest | 29141.36030 | 1 | 0 | 37357.672966 | -8216.312666 |

1338 rows × 9 columns

6.4. Scikit-learn regression models¶

Scikit-learn lets you perform linear regression in Python in a different way.

When it comes to machine learning in Python, Scikit-learn (or SKLearn) is the gold standard. There are many learning techniques available for regression, classification, clustering, and dimensionality reduction.

To use linear regression, we first need to import it:

from sklearn import linear_model

Let us use the same insurance cost dataset as before. Importing the datasets from SKLearn and loading the insurance dataset would initially be the same procedure:

df = pd.read_csv('/Users/Kaemyuijang/SCMA248/Data/insuranceKaggle.csv')

6.4.1. Create a model and fit it¶

In a simple linear regression, there is only one input variable and one output variable.

First Let us take age as the input variable and charges as the output. We will define our x and y.

We then import the LinearRegression class from Scikit-Learn’s linear_model. Then you can instantiate a new LinearRegression object. In this case it was called lm.

# Creating new variables

x=df[['age']] #a two-dimensional array

y=df['charges'] #a one-dimensional array

# Creating a new model

lm = linear_model.LinearRegression()

print(x.shape)

print(y.shape)

(1338, 1)

(1338,)

The .fit() function fits a linear model. We want to make predictions with the model, so we use .predict():

Note The method requires two arrays: X and y, according to the help documentation. The capital X denotes a two-dimensional array, whereas the capital Y denotes a one-dimensional array.

# fit the model

lm_model = lm.fit(x,y)

# Make predictions with the model

predictions = lm_model.predict(x)

df['slr_result'] = predictions

df['slr_error'] = df['charges'] - df['slr_result']

Note that .predict() uses the linear model we fitted to predict the y (dependent variable).

You have probably noticed that when we use SKLearn to perform a linear regression, we do not get a nice table like we do with Statsmodels.

We may return the score, coefficients, and estimated intercepts by using built-in functions. Let us take a look at how it works:

The following code returns the R-squared (or the coefficient of determination) score. This is the proportion of explained variation of the predictions, as you may remember.

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

r2_score(y.values , predictions)

0.08940589967885804

# alternative to r2_score

lm.score(x,y)

0.08940589967885804

print ('Slope: ', lm.coef_)

print ('Intercept: ',lm.intercept_)

Slope: [257.72261867]

Intercept: 3165.885006063021

The results of the regression analysis, including the R-squared, slope, and intercept, are the same as for statsmodel.

6.4.2. The algorithm’s evaluation¶

The final stage is to evaluate the algorithm’s performance.

This phase is especially significant when comparing the performance of multiple algorithms on a given data set. Regression methods are often evaluated using three metrics:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is the mean of the absolute value of the errors. It is calculated as:

where \(\hat{y}_{i}\) is the prediction and \(y_{i}\) the true value.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) is the mean of the squared errors and is calculated as:

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is the square root of the mean of the squared errors:

Fortunately, we do not have to do these calculations manually. The Scikit-Learn library has pre-built functions that we can use to determine these values for us.

Let us determine the values for these metrics using our test data. Run the following code:

from sklearn.metrics import *

print('Mean Absolute Error:', mean_absolute_error(y.values , predictions))

print('Mean Squared Error:', mean_squared_error(y.values , predictions))

print('Root Mean Squared Error:', np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y.values , predictions)))

Mean Absolute Error: 9055.14962050455

Mean Squared Error: 133440978.61376347

Root Mean Squared Error: 11551.66562075632

#Alternatively,

output_df = pd.DataFrame(columns=['MAE','MSE','R2-Score'],index=['Linear Regression','Multiple Linear Regression'])

output_df['MAE']['Linear Regression'] = np.mean(np.absolute(predictions - y.values))

output_df['MSE']['Linear Regression'] = np.mean((predictions - y.values) ** 2)

output_df['R2-Score']['Linear Regression'] = r2_score(y.values , predictions)

output_df

| MAE | MSE | R2-Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 9055.149621 | 133440978.613763 | 0.089406 |

| Multiple Linear Regression | NaN | NaN | NaN |

In all three approaches, the errors are calculated by taking the difference between predicted values and actual value, and the lower the difference, the better.

The primary distinction is that MSE/RMSE punish large errors and are differentiable, whereas MAE is not, making it difficult to use in gradient descent.

RMSE, in contrast to MSE, takes the square root, preserving the original data scale.

Exercise

Perform a regression analysis using scikit-learn with the multiple regression model with age, bmi, and smoker as predictors.

Evaluate the model using the three matrices MAE, MSE, RMSE and store the values in the DataFrame output_df.

6.5. Multivariate Linear Regression in Scikit-Learn¶

We will perform linear regression using multiple variables.

Scikit-Learn makes creating these models a breeze. Remember passing a two-dimensional array x when you originally trained your model?

In that array, there was only one column.

To match your data with multiple variables, you can simply pass in an array with multiple columns. Let us take a look at how this works:

6.5.1. Categorical variable encoding¶

df = pd.read_csv('/Users/Kaemyuijang/SCMA248/Data/insuranceKaggle.csv')

# Categorical variable encoding

df_encoding1 = pd.get_dummies(data=df, columns=['smoker','sex'], drop_first=True)

# print(df.head())

# df_encoding1.head()

# rename the column names

df_encoding1 = df_encoding1.rename(columns={"smoker_1":"smoker_yes","sex_1":"sex_male"})

df_encoding1

| age | bmi | children | region | charges | smoker_yes | sex_male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | southwest | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | southeast | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | southeast | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | northwest | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | northwest | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1333 | 50 | 30.970 | 3 | northwest | 10600.54830 | 0 | 1 |

| 1334 | 18 | 31.920 | 0 | northeast | 2205.98080 | 0 | 0 |

| 1335 | 18 | 36.850 | 0 | southeast | 1629.83350 | 0 | 0 |

| 1336 | 21 | 25.800 | 0 | southwest | 2007.94500 | 0 | 0 |

| 1337 | 61 | 29.070 | 0 | northwest | 29141.36030 | 1 | 0 |

1338 rows × 7 columns

# Creating new variables

x=df_encoding1[['age','bmi','smoker_yes']]

y=df_encoding1['charges']

# Creating a new model and fitting it

multi = linear_model.LinearRegression()

multi_model = multi.fit(x, y)

predictions = multi_model.predict(x)

df_encoding1['mlr_result'] = predictions

mlr_error = y - predictions

df_encoding1['mlr_error'] = mlr_error

print ('Slope: ', multi_model.coef_)

print ('Intercept: ',multi_model.intercept_)

print("Mean absolute error: %.2f" % np.mean(np.absolute(predictions - y.values)))

print("Residual sum of squares (MSE): %.2f" % np.mean((predictions - y.values) ** 2))

print("R2-score: %.2f" % r2_score(y.values , predictions) )

output_df['MAE']['Multiple Linear Regression'] = np.mean(np.absolute(predictions - y.values))

output_df['MSE']['Multiple Linear Regression'] = np.mean((predictions - y.values) ** 2)

output_df['R2-Score']['Multiple Linear Regression'] = r2_score(y.values , predictions)

Slope: [ 259.54749155 322.61513282 23823.68449531]

Intercept: -11676.830425187785

Mean absolute error: 4216.78

Residual sum of squares (MSE): 37005395.75

R2-score: 0.75

Again, the results of the multiple regression analysis, including the R-squared, the coefficients, and the intercept, are the same as for statsmodel.

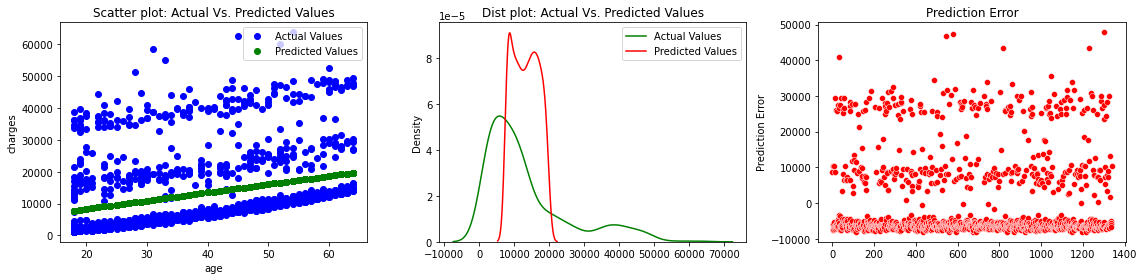

6.5.2. Visualize Predictions Of Multiple Linear Regression with Plotnine¶

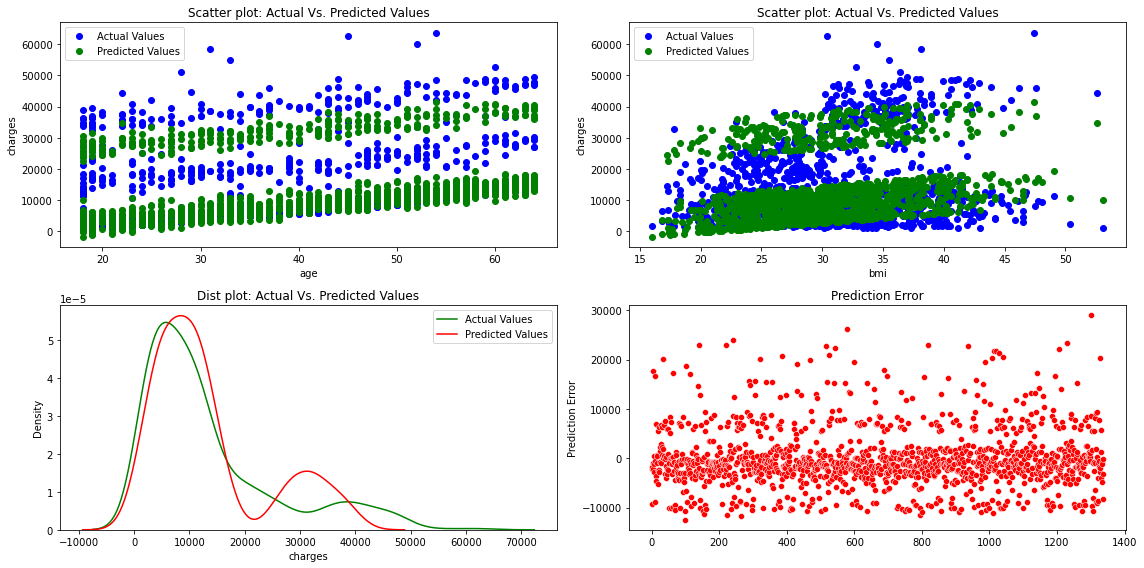

fig, axes =plt.subplots(2,2, figsize=(16,8))

axes[0][0].plot(x['age'], y,'bo',label='Actual Values')

axes[0][0].plot(x['age'], predictions,'go',label='Predicted Values')

axes[0][0].set_title("Scatter plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[0][0].set_xlabel("age")

axes[0][0].set_ylabel("charges")

axes[0][0].legend()

axes[0][1].plot(x['bmi'], y,'bo',label='Actual Values')

axes[0][1].plot(x['bmi'], predictions,'go',label='Predicted Values')

axes[0][1].set_title("Scatter plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[0][1].set_xlabel("bmi")

axes[0][1].set_ylabel("charges")

axes[0][1].legend()

sns.distplot(y, hist=False, color="g", label="Actual Values",ax=axes[1][0])

sns.distplot(predictions, hist=False, color="r", label="Predicted Values" , ax=axes[1][0])

axes[1][0].set_title("Dist plot: Actual Vs. Predicted Values")

axes[1][0].legend()

sns.scatterplot(x=y.index,y='mlr_error',data=df_encoding1,color="r", ax=axes[1][1])

axes[1][1].set_title("Prediction Error")

axes[1][1].set_ylabel("Prediction Error")

fig.tight_layout()

/Users/Kaemyuijang/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/seaborn/distributions.py:2619: FutureWarning: `distplot` is a deprecated function and will be removed in a future version. Please adapt your code to use either `displot` (a figure-level function with similar flexibility) or `kdeplot` (an axes-level function for kernel density plots).

/Users/Kaemyuijang/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/seaborn/distributions.py:2619: FutureWarning: `distplot` is a deprecated function and will be removed in a future version. Please adapt your code to use either `displot` (a figure-level function with similar flexibility) or `kdeplot` (an axes-level function for kernel density plots).

df_encoding1.head()

| age | bmi | children | region | charges | smoker_yes | sex_male | mlr_result | mlr_error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 27.900 | 0 | southwest | 16884.92400 | 1 | 0 | 26079.218615 | -9194.294615 |

| 1 | 18 | 33.770 | 1 | southeast | 1725.55230 | 0 | 1 | 3889.737458 | -2164.185158 |

| 2 | 28 | 33.000 | 3 | southeast | 4449.46200 | 0 | 1 | 6236.798721 | -1787.336721 |

| 3 | 33 | 22.705 | 0 | northwest | 21984.47061 | 0 | 1 | 4213.213387 | 17771.257223 |

| 4 | 32 | 28.880 | 0 | northwest | 3866.85520 | 0 | 1 | 5945.814340 | -2078.959140 |

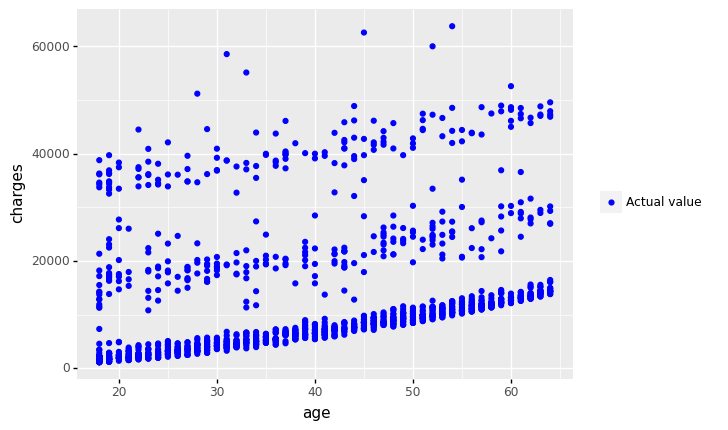

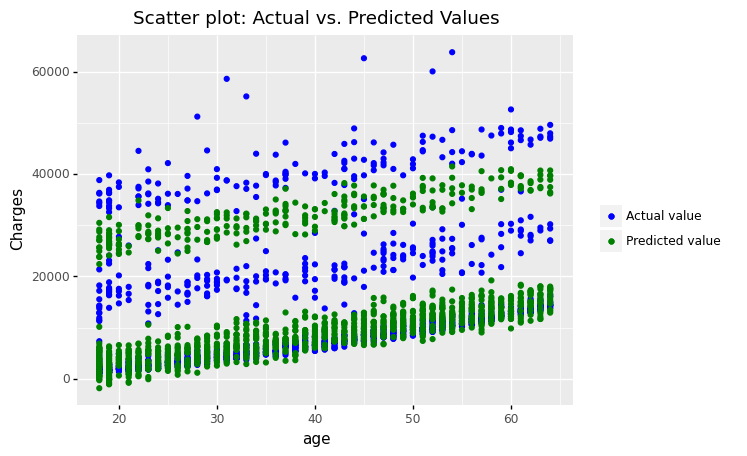

(

ggplot(df_encoding1)

+ geom_point(aes(x = 'age', y='charges',color='"Actual value"'))

+ geom_point(aes(x = 'age', y='mlr_result',color='"Predicted value"'))

#+ geom_smooth(aes(x = 'bmi', y = 'mlr_result', color='"Predicted value"'))

+ scale_color_manual(values = ['blue','green'], # Colors

name = " ")

+ labs(y='Charges', title = 'Scatter plot: Actual vs. Predicted Values')

)

<ggplot: (306833141)>

(

ggplot(df_encoding1)

+ geom_point(aes(x = 'bmi', y='charges',color='"Actual value"'))

+ geom_point(aes(x = 'bmi', y='mlr_result',color='"Predicted value"'))

#+ geom_smooth(aes(x = 'bmi', y = 'mlr_result', color='"Predicted value"'))

+ scale_color_manual(values = ['blue','green'], # Colors

name = " ")

+ labs(y='Charges', title = 'Scatter plot: Actual vs. Predicted Values')

)

<ggplot: (305165713)>

(

ggplot(df_encoding1, aes(x='charges'))

+ geom_density(aes(y=after_stat('density'),color='"Actual Values"' ))

+ geom_density(aes(x='mlr_result',y=after_stat('density'),color='"Predicted Values"'))

+ scale_color_manual(values = ['green','red'], name = 'Legend')

+ labs(title = 'Distribution plot: Actual vs. Predicted Values')

)

<ggplot: (311690677)>

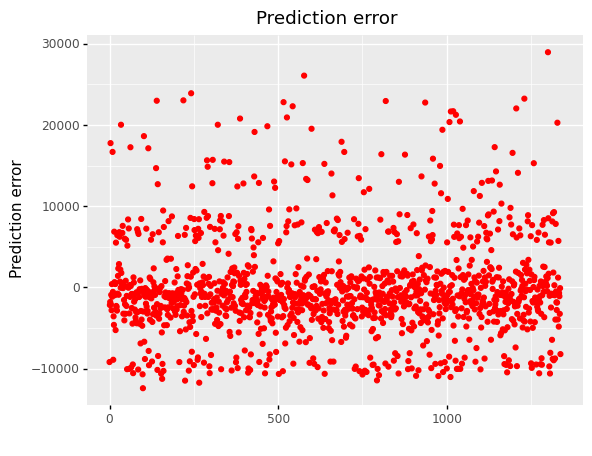

(

ggplot(df_encoding1, aes(x='df.index'))

+ geom_point(aes(y='mlr_error'),color='red')

+ labs(x = ' ', y='Prediction error')

+ labs(title = 'Prediction error')

)

<ggplot: (304769825)>

6.5.3. Compare Results and Conclusions¶

The error distribution can be used to assess the quality of a linear regression model (details given elsewhere). Quantitative measurements like MAE, MSE, RMSE, and R squared are also available for model comparison.

print(output_df)

MAE MSE R2-Score

Linear Regression 9055.149621 133440978.613763 0.089406

Multiple Linear Regression 4216.775692 37005395.750508 0.747477

6.5.3.1. Conclusions¶

By comparing the simple linear regression and multiple linear regression models, we conclude that the multiple linear regression is the best model, achieving 74.75% accuracy (R-squared).

In this situation, an R-squared value of 0.7475 indicates that the multiple linear regression model explains 74.75 percent of the variation in the target variable, which is generally considered as a good rate.

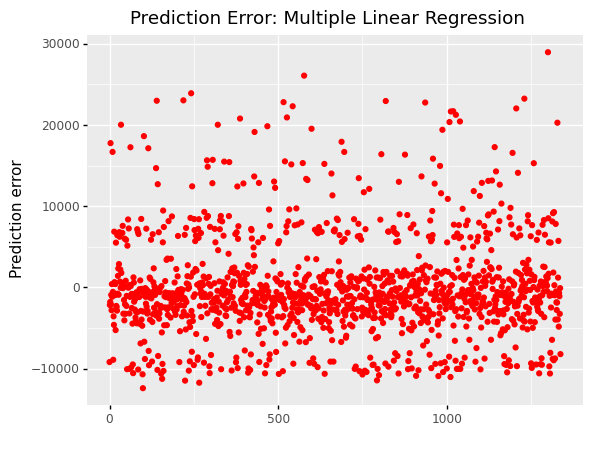

When we look at error graphs, we can see that

The error varies from -10,000 to 50,000 in simple linear regression.

The error ranges from -10,000 to 30,000 in Multiple Linear Regression.

#(

# ggplot(df, aes(x='df.index'))

# + geom_point(aes(y='slr_error'),color='red')

# + labs(x = ' ', y='Prediction error')

# + labs(title = 'Prediction Error: Linear Regression')

#)

(

ggplot(df_encoding1, aes(x='df.index'))

+ geom_point(aes(y='mlr_error'),color='red')

+ labs(x = ' ', y='Prediction error')

+ labs(title = 'Prediction Error: Multiple Linear Regression')

)

<ggplot: (309356937)>